According to MDN, a Promise, in JavaScript, is an object that represents the eventual completion (or failure) of an asynchronous operation and its resulting value. But what does that actually mean and how do promises work?

An analogy

I went to Bangalore a few weeks back with my friend Steve. He was moving there and was going to house hunt, and I tagged along. We reached the railway station early morning and had to wait a bit more at the station before we could go to the stay we had booked.

We got hungry and since none of the in-station canteens had opened yet, we decided to order some food. Both of us had different cravings, so we ordered separately and waited. Delivery agents were short in number as the city was just waking up. After some 20 minutes, agents were assigned to our orders and our food was on their way.

Our apps informed us, or rather promised us, that our food would be delivered within 30 minutes. A few minutes later, I got a call from a customer care executive informing me that my delivery agent got a flat tire and wouldn't be able to fulfill the delivery. My order was then canceled and the refund process was initiated. So at the end of 30 minutes, Steve was munching on his noodles while I was on the app again, with an empty stomach, about to place another order.

From a high level, Promises in JavaScript resemble real-life promises. The app promised us that our food would get delivered. We then waited while the app and its delivery agents did their thing, and out of the two promises, the promise made to Steve was fulfilled, while the one made to me wasn't.

Why do Promises exist?

Promises come to play in the world of async programming. Consider this code snippet.

console.log('hi there!');

fetch('https://exampleapi.com/hola')

.then(res => res.json())

.then(data => console.log(data))

.catch(error => console.log('ERROR: ', error));

console.log('hi again!');

for (let i = 0; i < 10; ++i)

console.log('hehe')

The snippet can be thought of as three blocks

- The first block has a single

console.log()statement - The second block makes a

fetch()request to an API and then displays the data received as the response. An error handler (catch) is also added in case an error is thrown. - The third block has a

console.log()statement followed by aforloop.

JavaScript, by its true nature, is single-threaded i.e. it can only execute one piece of code at a time. This implies that if I have five sequential lines of code, then line three will only be executed after lines one and two. However, this introduces a problem. What if one of the lines takes a bit too long to execute?

Out of the three "blocks" of code mentioned above, the second block has the potential to be time-consuming as some APIs take considerable time to return a response. Assume that our example API takes 5seconds to return a response. If JavaScript followed its single-threaded mantra, code execution would pause at the fetch statement for 5 seconds and only then continue to the third block. The third block is completely independent of the second block, but now its execution is delayed by 5 seconds. This behavior has major performance and user experience concerns.

What could be a solution to this problem? Since the third block is independent of the time-consuming second block, wouldn't it be nice if we could make the API call and then instead of waiting to get the response, use that time effectively by executing the third block? And when the API returns a response, JavaScript could go back to the second block and start executing the rest of the code in the block.

That's what async programming is in a nutshell and Promises help us to execute code in this manner. We have a caller (the fetch() method) and a callee (the API endpoint). Since we don't get an immediate result when the caller makes the call, the callee returns a temporary value - the promise object, which promises the caller that a proper response will be available at a future point in time. When the response is received, code execution goes back to the caller.

The Three States

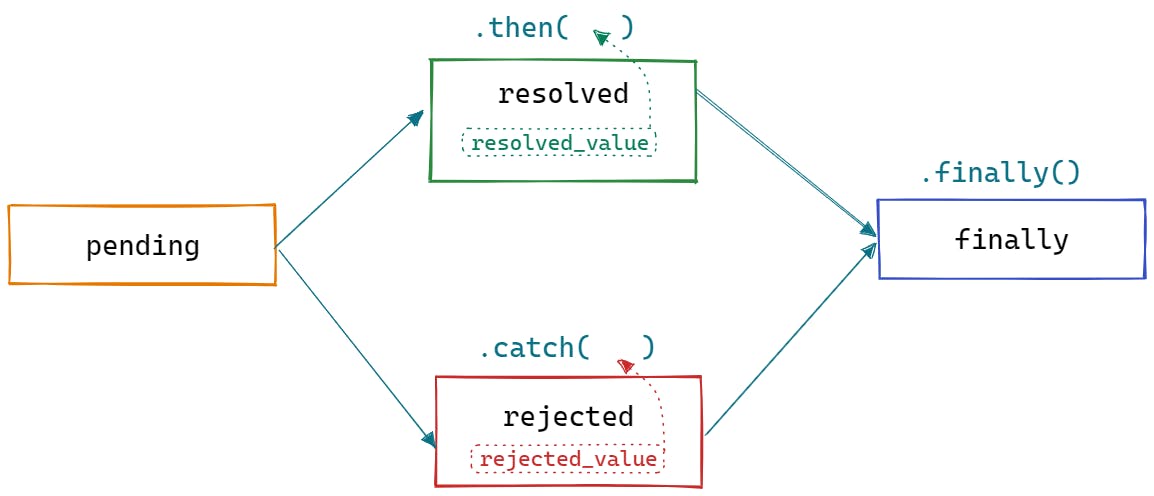

A Promise can have one of three states

- Pending - when it is initialized or waiting to get fulfilled or rejected

- Fulfilled - successful completion of the operation

- Rejected - failed operation

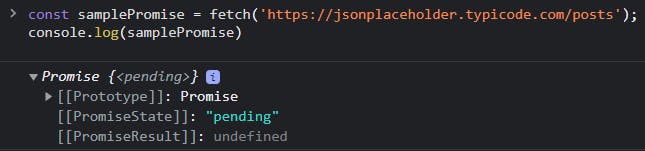

To test this, open the dev tools in the browser, go to the Network tab, and set the network speed to "Slow 3G'. This mimics a slow connection. Then go to the console tab and run this script

const samplePromise = fetch('https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users');

console.log(samplePromise)

The Promise object will be in the pending state

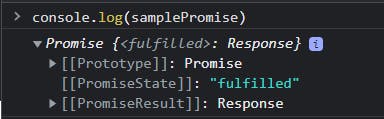

After a few seconds, console log the samplePromise object again. It will now be in the fulfilled state.

Then, Catch & Finally

then, catch and finally are methods that we can register on the promise.

The first two methods work depending on the states of the Promises. then for when the Promise is fulfilled and catch when it is rejected. And finally (pun intended) finally is executed always, irrespective of whether the promise was fulfilled or rejected.

const samplePromise = fetch('https://jsonplaceholder.typicode.com/users');

samplePromise

.then(resolved => resolved.json())

.then(jsonData => console.log(jsonData))

.catch(error => console.log('that did not work'))

.finally(() => console.log('operations complete'))

The above snippet would log out the API response and then finally log out the string 'operations compete'

If you make a slight modification to the API URL (jsonplaceholder to jsonplaceholders) and run the script, you'll get the error message and then the string 'operations complete'

When the .then() method is called by the promise, it passes a 'resolved value' as the argument for the method. Similarly, when an error is thrown, a 'rejected value' is passed as the argument for the catch method. The finally() method accepts no arguments.

Creating Promises

More often that not, you will be consuming promises created by other functions or services. The fetch method we've been using so far is a good example of the consumption of promises.

But Promises can also be created manually by calling the new Promise() constructor.

We pass in one function as the argument for the constructor. This function is called the executor function. It is automatically called when the Promise is created.

The execution function itself takes in two callback functions as its arguments -> resolve and reject. If the resolve callback is called, the Promise is fulfills and if the reject callback is called, it rejects.

The argument that's passed in when the resolve and reject callbacks are called become the resolved and rejected values of the promise respectively and thereby the parameters for the .then and .catch methods.

Try executing this below snippet a couple of times. The Promise resolves or rejects randomly based on the value of the value variable.

const promise = new Promise(function(resolve, reject) {

const value = Math.random();

console.log(value)

if (value > 0.5)

resolve('you shall pass');

else

reject('you shall not pass')

});

promise

.then(resolved => console.log(resolved))

.catch(rejected => console.log(rejected))

If you enjoyed reading this, do consider checking out my other articles too. Feel free to connect with me on Twitter as well. I'd love to chat!